I like to make burritos -- burritos for breakfast, lunch, dinner, early morning surf trips, you name it. Burritos can be vegetarian, with just rice and beans and salsa and lots of cilantro. Burritos can be spicy, with Dave's Insanity Sauce (caution -- just looking at a bottle of this sauce can make your hair start to stand up and your eyes begin to water). Burritos can be filled with leftovers and wrapped in tinfoil to take to work the next day (especially if you have a toaster-oven where you work). And, in case I haven't said it before, burritos can be wrapped up and taken with you on the drive to the local break for an early-morning surf session (along with a big travel mug of hot black coffee).

I grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area, where the Mission-style burrito (originating in the Mission district of San Francisco) is a work of art, and different taquerias have their own unique style and loyal followings. But because I have lived all over the country -- often in places where they do not have taquerias that serve Mission burritos -- I have had to learn how to roll my own. Once you know the proper sequence of moves, it's not difficult at all to roll a great burrito, but it helps to have the right kind of tortilla. I've tried just about every tortilla sold in stores, and my favorites are the really big, extra-large and extra-thin tortillas that have writing in Spanish all over the packages.

However, the sad fact of the matter is that just about every tortilla you will encounter in just about every supermarket in California likely contains genetically-modified ingredients, unless you are in an organic grocery store or a Trader Joe's (which promises no GMOs in foods carried under their Trader Joe's product label).

***

Editor's note: what does any of this have to do with the subject matter of this blog? It has quite a lot to do with it, because it is about looking at the evidence for yourself, analyzing the various things that people are telling you, and making your own decisions about what to believe -- doing your own "due diligence."

***

Editor's note: what does any of this have to do with the subject matter of this blog? It has quite a lot to do with it, because it is about looking at the evidence for yourself, analyzing the various things that people are telling you, and making your own decisions about what to believe -- doing your own "due diligence."

***

There are currently eight GM foods authorized for sale as human food or ingredients in human food in the US (for more discussion and links to resources about these eight crops, see this previous post):

- corn (a huge percentage of which is now GM in the US, as well as all the varied corn products made from GM corn, including corn syrups, corn starches, corn oils, etc)

- soy

- cottonseed (consumed by humans as cottonseed oil)

- canola

- sugarbeets (and therefore most sugar and foods containing sugar as an ingredient, unless it specifically says "cane sugar")

- more than half of Hawaiian papaya (some sources now say 80% of it)

- a small percentage of zucchini

- a small percentage of yellow crookneck squash.

Try going into any of your local supermarkets and looking through every package of tortillas that they have for sale. Every single package, from every single brand, will probably contain corn, cottonseed oil, or both. If they are not labeled as "organic" or "contains no GMO ingredients," then you can assume that the cottonseed oil and the corn come from genetically modified plants. Most typical supermarket chains carry several brands of tortillas, but typically not one of those brands in the store will be organic or state that its ingredients do not come from GMO sources.

Perhaps this is just because there really isn't a market for tortillas made without genetically-modified ingredients. Perhaps people just don't care. After all, if people rebelled against genetically-modified tortillas on their burritos, then nobody would buy those tortillas and the stores would stop selling them, or the tortilla brands would start offering some non-GMO tortillas as an option.

That's a great argument, but if the companies believe that people don't care about GMO ingredients, then why are so many of them spending so many millions of dollars to try to prevent the labeling of all foods that contain GMO ingredients? If they really don't care, then adding the words, "Partially Produced with Genetic Engineering" or "May be Partially Produced with Genetic Engineering" should not be such a big deal to shoppers, by that argument. More on that in a moment.

Perhaps you do not fancy burritos to the same extent that I do, but if you head over just a few aisles to the Asian food section (where I also like to spend a lot of time), you will find a similar predicament when trying to purchase soy sauce in most grocery stores. You will find a host of different soy sauce brands, as well as some "low-sodium" options and some "lite" options, but unless you are shopping in an organic store or other specialty grocer, you will probably not find a single soy sauce that states that it does not contain genetically-modified ingredients. You can generally take that as a sign that the soy sauce was made with transgenic soy, at least if you are shopping in the United States, where over 90% of soy grown for human consumption is genetically modified.

And, if you get frustrated at this dilemma, wondering how you will make your stir-fry without any soy sauce, and you decide to purchase some pre-made stir-fry sauce (maybe some General Tso's sauce, or some teriyaki or some sesame-ginger sauce or something) to use in place of soy sauce until you can get down to the organic food store or the Trader Joe's and buy some non-GMO soy sauce, good luck finding one that is not made with soy, or with high-fructose corn syrup, or with sugar.

Since high-fructose corn syrup is made from corn, almost all of which is now genetically-engineered in the US, and since more and more sugar beets will now be genetically-engineered, and since (as we've already seen) the vast majority of soy is GMO (and soy is an ingredient in just about every sauce product in the Asian aisle of the grocery store), you won't be able to get out the door without some GMO ingredients to add to your stir-fry, if you shop in most grocery stores in America today.

But that's no problem, because nobody really cares about consuming GMO ingredients, right? Again, if that's the case, why are so many powerful interests lining up to prevent the labeling of foods that might have been produced or "partially produced" with genetic engineering?

Could it be that those powerful interests understand that the real reason most consumers don't have a hard time shopping for tortillas or soy sauce is that most consumers are completely unaware of the extent to which every product they are comparing already contains GMOs? Labeling, such as the labeling that would be required in California if Proposition 37 passes this November, would lift the veil on this situation, and would open a lot of consumers' eyes to the fact that they are purchasing a lot more food made with genetically-engineered ingredients than they currently could imagine.

The campaign to prevent this from happening -- to prevent consumers from being told if a product contains genetically-engineered ingredients -- is just beginning to produce advertisements, but there is little doubt that they will be ramping up in earnest over the coming weeks. This "No on 37" website contains links to videos, most of which contain reassuring messages from doctors (all of whom are no doubt well-intentioned and sincere in their opinion that genetically-modified foods are safe for human consumption), such as the video below:

Perhaps this is just because there really isn't a market for tortillas made without genetically-modified ingredients. Perhaps people just don't care. After all, if people rebelled against genetically-modified tortillas on their burritos, then nobody would buy those tortillas and the stores would stop selling them, or the tortilla brands would start offering some non-GMO tortillas as an option.

That's a great argument, but if the companies believe that people don't care about GMO ingredients, then why are so many of them spending so many millions of dollars to try to prevent the labeling of all foods that contain GMO ingredients? If they really don't care, then adding the words, "Partially Produced with Genetic Engineering" or "May be Partially Produced with Genetic Engineering" should not be such a big deal to shoppers, by that argument. More on that in a moment.

Perhaps you do not fancy burritos to the same extent that I do, but if you head over just a few aisles to the Asian food section (where I also like to spend a lot of time), you will find a similar predicament when trying to purchase soy sauce in most grocery stores. You will find a host of different soy sauce brands, as well as some "low-sodium" options and some "lite" options, but unless you are shopping in an organic store or other specialty grocer, you will probably not find a single soy sauce that states that it does not contain genetically-modified ingredients. You can generally take that as a sign that the soy sauce was made with transgenic soy, at least if you are shopping in the United States, where over 90% of soy grown for human consumption is genetically modified.

And, if you get frustrated at this dilemma, wondering how you will make your stir-fry without any soy sauce, and you decide to purchase some pre-made stir-fry sauce (maybe some General Tso's sauce, or some teriyaki or some sesame-ginger sauce or something) to use in place of soy sauce until you can get down to the organic food store or the Trader Joe's and buy some non-GMO soy sauce, good luck finding one that is not made with soy, or with high-fructose corn syrup, or with sugar.

Since high-fructose corn syrup is made from corn, almost all of which is now genetically-engineered in the US, and since more and more sugar beets will now be genetically-engineered, and since (as we've already seen) the vast majority of soy is GMO (and soy is an ingredient in just about every sauce product in the Asian aisle of the grocery store), you won't be able to get out the door without some GMO ingredients to add to your stir-fry, if you shop in most grocery stores in America today.

But that's no problem, because nobody really cares about consuming GMO ingredients, right? Again, if that's the case, why are so many powerful interests lining up to prevent the labeling of foods that might have been produced or "partially produced" with genetic engineering?

Could it be that those powerful interests understand that the real reason most consumers don't have a hard time shopping for tortillas or soy sauce is that most consumers are completely unaware of the extent to which every product they are comparing already contains GMOs? Labeling, such as the labeling that would be required in California if Proposition 37 passes this November, would lift the veil on this situation, and would open a lot of consumers' eyes to the fact that they are purchasing a lot more food made with genetically-engineered ingredients than they currently could imagine.

The campaign to prevent this from happening -- to prevent consumers from being told if a product contains genetically-engineered ingredients -- is just beginning to produce advertisements, but there is little doubt that they will be ramping up in earnest over the coming weeks. This "No on 37" website contains links to videos, most of which contain reassuring messages from doctors (all of whom are no doubt well-intentioned and sincere in their opinion that genetically-modified foods are safe for human consumption), such as the video below:

As discussed in previous blog posts on this subject, there are many who argue that genetically-engineered foods are not harmful to humans, including the doctors in the above video. However, what is not mentioned in these videos is the possibility that genetically-engineered foods (which almost always use genetic material from viruses and bacteria) may be harmful to the symbiotic bacteria which live inside of us and which are essential to human life and health. There are also concerns that these modifications may be harmful to human genetic material or directly harmful to humans in other ways. Some people may say that such fears are ridiculous, or unscientific, but shouldn't each shopper be allowed to make an informed decision on that question for himself or herself?

The "No on 37" website where this video originated argues that such labeling would be costly and that it would raise prices for everyone without giving them any useful information. This 52-page report, linked on the website, makes that argument. These arguments get closer to the heart of the issue.

Concerns over the cost of food to the consumer is a valid point, but the real issue is the cost to the producer of the food, and the cost of keeping GMO and non-GMO foods separate (if labeling is suddenly required). The consumer is currently being asked to accept the idea that GMO foods are nothing to worry about, in order to save money for the companies involved in growing these foods. The argument is that unless consumers accept such ingredients, it will be impossible to provide food.

But this is a false argument. To use an analogy from a text written long before genetically-modified foods were invented, this is like trucking companies arguing that they cannot effectively deliver goods around the country unless they are permitted to drive over the front lawns of houses when the roads are congested. If such an assertion is accepted, and everyone allows truckers to drive their big rigs over their home's front lawn whenever they feel like it, then that system will come to be seen as inevitable. However, if the laws protect citizens from the uncompensated intrusion of trucks on their property, then trucking companies will have to come up with systems to get goods where they need to go without driving all over people's front yards -- and what's more, trucking companies will come up with those systems!

The argument that "It's just too difficult to deliver non-GMO foods anymore" is exactly this sort of false argument, and yet it is one that will increasingly be heard as the debate over Prop 37 heats up. Below is an example of such an argument:

This argument basically says to consumers, "GMO ingredients are everywhere, and there's no going back. Therefore, don't ask us to label them." This is at least a more honest approach than saying, "GMO foods are safe, and therefore we shouldn't label them." This argument is saying that so much of our food supply now has GMO in it that it is just too hard to label it all.

The "too hard" excuse, however, does not withstand concerted analysis, however. The government does not seem to have any problem forcing every tobacco product to carry a label, no matter how difficult it is to do so. The government also requires all foods to contain detailed lists of their ingredients, calories per serving, grams of total fat, saturated fat, trans fat, cholesterol, sodium, carbohydrate (broken down into dietary fiber and sugars) and percentages of the USDA recommended daily allowances of a variety of vitamins and minerals.

Perhaps it would be more accurate to read between the lines, and to say that when someone argues that "GMO ingredients are everywhere -- therefore it's too hard to label them all," what they are really saying is that "GMO ingredients are everywhere -- if we labeled them all, we might cause a panic."

However, because there are alternatives available on the market, this argument also does not hold water. Even opponents of GMO labeling admit that consumers who are concerned about genetically-modified ingredients in their food can seek out alternatives, such as organic foods (even if labeling opponents feel such concerns are misguided, since GMOs are totally safe, in their opinion). If everything that contained genetically-modified ingredients were labeled, it is likely that the demand for such organic foods (and other alternatives that announced they did not use GMOs in their ingredients) would increase.

Opponents of GMO labeling argue that it would be a "hidden food tax that would especially hurt seniors and low-income families who can least afford it," but the fact is that the food companies are probably enjoying the business of many "seniors and low-income families" who are currently buying GMO products (such as tortillas) because they have no idea that they are buying GMO ingredients. In other words, the companies that sell these foods to these groups are able to sell more such foods than they might be able to sell if labeling laws were passed -- because their products would become less attractive.

If that happened, foods with GMO ingredients might have to lower their prices in order to compete with the alternatives that they do not have to compete against right now to the same degree. In other words, certain consumers may already be paying more for foods which enjoy less competition than they would face once those consumers learn the truth about what's in their food.

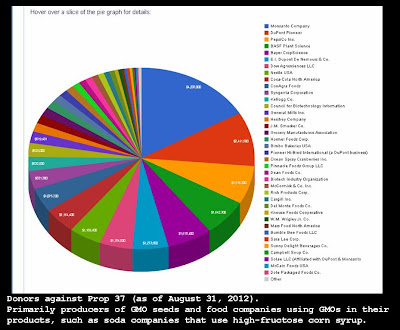

The list of donors contributing money for organizations seeking to dissuade voters from passing Prop 37 in California tends to support the conclusion that the real opposition to the labeling of GMO foods comes from companies whose businesses directly benefit from the use of GMO ingredients or the sale of GMOs themselves (the chemical companies who have patented seeds and plants containing transgenic traits). The pie charts below show the current list of donations to both sides of Prop 37:

As of publication of this post on August 31 of 2012, the donors against who are named on the chart have contributed $25,075,009. The largest donor is also the largest producer of genetically-modified organisms and has contributed over $4.2 million to date. Other donors include big soda companies (which use a lot of high-fructose corn syrup in their products, as well as sugar, both of which are largely produced from crops with large percentages of GM plants, such as corn and sugar beets).

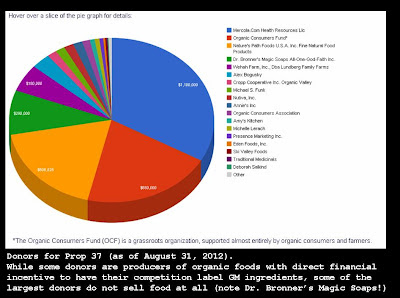

In contrast, the pie chart below shows donors who have contributed money to persuade for the labeling requirements in Prop 37, as of August 31:

The largest donor on the "yes" side, Dr. Mercola, does sell some health products, but they are primarily in areas that do not compete directly against products with GMO ingredients (the eight genetically-engineered plants listed above are not ingredients in most vitamins or supplements of the variety sold on Mercola websites). While the next two largest "yes" donors have a more-direct competitive interest in the issue, the fourth-largest donor, Dr. Bronner's Magic Soaps, does have a small line of all-natural snack bars, but is primarily known for selling soap and other personal-care body products, which are not in competition with food items. Further, it is clear from the two pie charts that the amounts given by the largest donors on the "no" side dwarf the contributions of the largest donors on the "yes" side (to date, the largest "yes" donor -- Mercola.com -- has given $1.1 million to support the labeling initiative).

To date, the donations to pass the labeling initiative from named entities on that website total only $3,294,326. In other words, the "no" donations outnumber the "yes" donations by about 7.6 to 1. This appears to be primarily due to the number of very large and well-capitalized corporations with an interest in defeating this initiative.

Strangely, none of the websites arguing against the labeling initiative voice what is perhaps the strongest argument for their position, which is the philosophical argument saying that the government should not use force to intrude upon the private property of citizens, including using force to make private companies or individuals place labels on products that they sell. This argument would say that private citizens who produce goods for sale should be allowed to offer those to other private citizens, who can choose to buy them or not buy them. If the buyers are concerned about the product, they can ask the maker of the product for details about it, and if they don't get an answer (or if they don't like the answer that they get), they can go elsewhere. This argument would say that the government does not have the right to infringe on the private property of the citizen in this way, forcing the citizen to slap a label on his or her goods, and doing so at the point of a gun (or at least with the threat of jail and other sanctions, where people are kept against their will and guarded by people with guns).

This would seem to be a very good argument indeed. The best counter to it would be an argument from the exact same principle, stating that the current state of affairs allows unwanted violation of property (including one's own body).

For starters, genetically-modified organisms, by their very nature, are able to reproduce and spread into other people's crops, which is a violation of property as well. That this takes place has already been demonstrated in courts of law. Therefore, citizens who wish to avoid GMOs by growing their own corn, soy, or canola on their own property may suddenly discover that they have some genetically-modified plants that invaded all by themselves.

Similarly, as the speaker in the last video embedded above makes clear, it is exceedingly difficult to keep GMO and non-GMO products separate in the "food stream" that he describes, leading to the situation in which GMO foods are basically shouldering their way into places and foods that they are "not invited." Further, because GMOs are a relatively new entrant into the food supply, it is quite possible that many consumers are not even aware that genetically-engineered ingredients are in their tortillas or their soy sauce (or a host of other products -- as many as 70% of all items on grocery shelves, according to the study linked above which was provided by the "No on 37" website and written by opponents of GMO labeling).

Because a vast majority of consumers are probably unaware that so many of the foods they are buying now contain genetically-modified organisms (when the same products did not just ten or fifteen years ago), it could be argued that this injection of GMOs into their food (and thence into their bodies) is similar to air pollution or water pollution and thus an invasion of their property (their body being included in that description).

Thus, while this line of argument (with some justification) says that governments should not tell companies and individuals what they can and cannot do with their property, including with products that they offer for sale, there is an obvious exception to that statement, which is that companies and individuals cannot invade the property of others in the process, which means that they cannot drive their trucks over peoples' lawns without permission, and they should not be allowed to invade their customers' bodies without their knowledge either (whether by pumping dangerous chemicals into the air their customers breathe, or by slipping potentially harmful DNA from viruses and bacteria into the corn, soy, canola, cottonseed, and sugarbeets that they eat, or that produce ingredients in other foods that they eat or drink).

There can be little doubt that if consumers knew that every tortilla and every bottle of soy sauce or teriyaki sauce in their supermarket contained genetically-engineered ingredients, some of them would seek other alternatives. There would probably be enough demand for such alternatives that supermarkets would begin to stock non-GMO alternatives next to all the GMO products in each of the various aisles of the store.

However, it is also clear that the truly staggering quantity of supermarket items which now contain GMO ingredients represents a new status quo that has numerous powerful defenders who will use a wide variety of methods to prevent this status quo from changing. These interests absolutely do not want labels which would reveal to consumers the extent to which their groceries contain genetically-modified organisms.

It will be very interesting to see how this fight turns out in California. It may be such an important issue that it will have repercussions for the rest of the world as well.