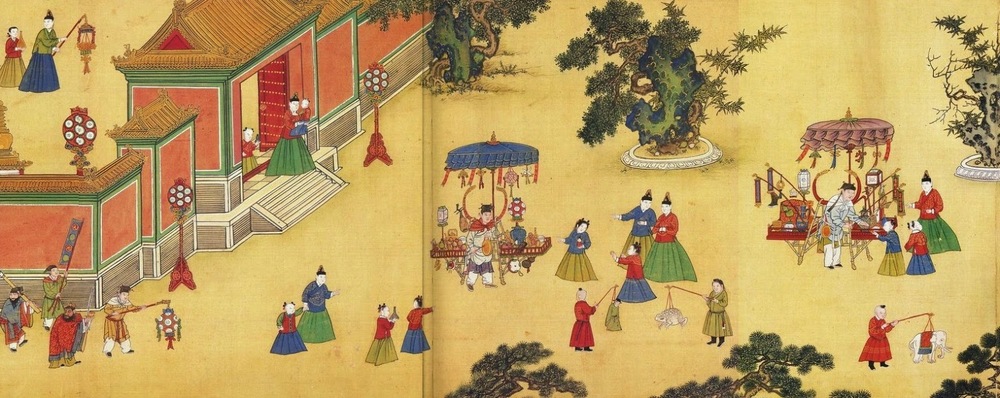

image: detail from Ming Dynasty painting, late 15th century, Wikimedia commons (link).

While on the subject of important festivals and holidays taking place this month, let's briefly discuss some of the significance of the traditional Chinese celebration of the Lantern Festival, which takes place each year on the night of the fifteenth day after the date of the lunar New Year.

Because the traditional lunar New Year takes place on the first New Moon after winter solstice, a festival timed to take place fifteen days after a New Moon is a festival which will always correspond to the Full Moon (for a discussion of the lunar New Year and moon cycles, see here, for example).

Thus we can immediately perceive that a celebration in which participants (and especially children) carry around lanterns through the streets and pathways and gardens underneath the first Full Moon of the year is declaring, establishing, and reinforcing a connection between the events taking place in the heavenly sphere and the events taking place here on earth, and between the motions of the heavenly bodies and our lives in these physical bodies: a proclamation of "as above, so below."

The image above, most likely painted in the year 1485, is a detail of a long series of painted panels showing the Ming Emperor Xianzong enjoying the Lantern Festival. To enjoy the entire painting, follow this link and then click on the image itself in order to enlarge it (until you do so, it will appear as a very thin strip across the top of the page, with its detail barely visible). Once you click on it, the entire series of episodes in the painting will be too wide to fit on most screens, so you can scroll left and right to view the entire painting, taking time to appreciate all the details included by the original artist, so many centuries ago.

In the image above, children can be seen carrying their lanterns suspended from long red poles. Some of the lanterns are in the shapes of animals or people, while others are more traditional globes with tassels. Vendors can be seen providing the lanterns to the children, from portable tables or booths, each with their own colorful canopies.

The progress of the moon, from New Moon to Full Moon, celebrated in the lunar New Year and the Lantern Festival, was understood by the ancient cultures around the world as conveying deep truths about our condition in this human life. Along with the motions of the sun, the planets, and the glorious backdrop of stars in the celestial sphere, the moon's monthly progress was understood as depicting for us the dual spiritual-physical nature of this universe we inhabit, and the dual spiritual-physical nature of our own human condition in this incarnate life.

In a short lecture on some of the spiritual truths that the ancients saw depicted in the motions of sun and moon, entitled Spiritual Symbolism of the Sun and Moon, Alvin Boyd Kuhn (1880 - 1963) said of the moon:

It is a reflector of the sun's light, and this reflection is made at night, when the sun is out of sight of man! The moon is our sun-by-night, and it is well to delve more deeply into the implications of this datum. The moon conveys to us the sun's light in our darkness. What does this mean on the wider scale of values? It means this: as the night typifies our time of incarnation, the diminished solar light reflected on the lunar surface is an index of the fact that by no means the full power and radiance of the sun (our divine light or spirit) can fall upon us or shine for us while in the life in body. As the moon stands for the body, the reflected light of the sun upon it and from it to us betokens that we can have access only to as much of the spiritual glory as our bodies can give passage to, or give expression to, or become susceptible to. In incarnation we are in spiritual darkness, or have access only to that spiritual force and radiance that can get down to us through the intervening medium of the physical mechanism. [. . .] When in incarnation, we are deprived of the full glow of our inner light. Our god is then as the hidden sun, and we must get its rays through a reflecting-medium, the body. [. . .] It thus also symbolizes the human body, which is surely not the light of spirit, yet in its structure and in its outward countenance, it reflects and bears witness to the divine spirit that animates it, the god hidden within. A man's spirit shines out on his face as the sun shines on the moon! 7 - 8.

Note that, as with other authors from previous generations, Kuhn is accustomed to using the term "man" to refer to "humanity," but that he is quite explicit, both in this lecture and in his other work, to indicate that he is referring to both men and women equally when discussing these great spiritual truths.

It is also important to note that Kuhn is not in any way indicating that he believes the moon's importance is somehow "lesser" as a heavenly teacher than the importance of the sun or any other heavenly light: he is simply saying that by nature of the moon's unique properties, the ancients saw it as perfect for conveying certain truths about our human condition that related to the fact that in these bodies we inhabit, our divine invisible spirit nature is hidden, and not seen directly or in full force. The contrast between the moon and the sun was seen as perfect for conveying that message.

Later in the same portion of his lecture, Kuhn goes on to explain that the moon was in no way inferior as a symbol of our human condition and as a teacher of our purpose in this life of remembering the spiritual that is within and behind everything physical that we see, in other beings and in ourselves, and calling forth the spirit, raising it up, and in doing so blessing them and creation:

But the most sublime element in the spiritual symbolism we are trying to depict comes next in the development of our theme. This is the eternal meaning connected with the sun's light on the moon that we are desirous of impressing in unforgettable vividness upon the imagination. This is the great fact which we would have you call to mind whenever you gaze upon the silvery orb from night to night. As the young crescent fills with light and rounds out its luminous circle, it is writing our spiritual history! It is preaching to us uncomprehending mortals the gospel truth about our own divination. The growing expanse of light on the moon, we repeat, is the sign, symbol and seal of our own transfiguration into godhood! The spark of divinity implanted in our organisms must, to use one Biblical figure, gradually leaven the whole lump; to use another, must illuminate the whole bodily house. [. . .] As we gaze upon the lunar crescent and see it go on toward the full, the vision should fortify us with the profoundest and sublimest truth about this mortal existence of ours, viz.: that we are in process of filling our very bodies with the mantling glow of an interior hidden light, which will steadily transform our whole nature with the beauty of its gleaming. 9.

The existence of Lantern Festivals such as that celebrated in China and other nearby countries and cultures on the fifteenth night after the lunar New Year "brings down" the message of the heavens to us here below, so that we can be reminded of our true condition as beings dwelling indeed in physical bodies, but possessed of an invisible, interior, submerged and hidden divine spark. The fact that children are the ones given the lanterns to carry about seems to emphasize this message -- their carrying about their "little moons" serves as a way of teaching it to them (through symbolism) and of reminding those of all ages who see this drama enacted each year of this message which the world always seems to be conspiring to make us forget.

Lest any skeptical readers doubt that the celestial connotations of this festival have long been part of the culture that observes this annual festival of lanterns, they should consider this beautiful poem by Xin Qiji

辛棄疾

(AD 1140 - AD 1207) which evokes the Lantern Festival and is "set to the Tune of the Jade Table" -- a very well-known poem in China:

东风夜放花千树,

更吹落,星如雨。

宝马雕车香满路,

凤箫声动,

玉壶光转,

一夜鱼龙舞。

蛾儿雪柳黄金缕,

笑语盈盈暗香去。

众里寻她千百度,

蓦然回首,

那人却在,

灯火阑珊处。

Personally, I am not currently capable of reading and translating all of that, but it is included for those who can, as translations inevitably must sacrifice some aspect of the poetry (here's the source). The translation found

here, from An Introduction to Chinese Literature by Liu Wu-chi (page 122), reads as follows:

At night the east wind blows open the blooms on a thousand trees,

And it blows down the stars that shower like rain.

Noble steeds and carved carriages -- the sweet flower scent covers the road;

The sound of the phoenix flute wafts gently;

The light of the jade vase revolves;

All night the fish and dragons dance.

Decked in moths, snowy willows, and yellow-gold threads,

She laughs and talks, then disappears like a hidden fragrance.

Among the crowds I have sought her a thousand times;

Suddenly as I turn my head around,

There she is, where the lantern light dimly flickers.

The possibility that the opening two lines of verse (which are rendered rather nicely in this translation as "One night's east wind adorns a thousand trees with flowers / and blows down stars in showers") refers to not only the lanterns of the festival but also the people themselves, who are themselves stars "blown down in showers" to earth and incarnation by the night's east wind (that is, a wind which originates in the east, but proceeds towards the west and thus towards the place of incarnation, where stars plunge beneath the western horizon, out of the heavens and into the realm of earth and water), would seem to be very defendable.

In other words, the poem evokes the Lantern Festival, and the poignant search for the woman the speaker has seen talking and laughing, but who disappears among the crowds . . . but it also evokes our condition in this incarnate life , in which we are like stars blown down from another world, searching for something of great beauty which we have glimpsed but lost among the jostling crowds of this physical world, but which we suddenly encounter again when we are least expecting it (perhaps when we are not even trying: in the peace of utter stillness).

Further support for the assertion that this poem is working on such multiple levels (even as the Lantern Festival itself is working on these multiple levels) can be found in the imagery of the "fish and dragons" in the final line of the first stanza, referring to the lanterns in the shapes of fish and dragons, carried by the revelers through the streets, but also evoking the tradition in China that carp can eventually transform into dragons. Both creatures, of course, have long barbels at their mouths, which suggests that dragons may once have been carp, or that carp may one day become dragons: but carp are creatures of water and hence represent our lower, human condition in these human bodies, seven-eighths of which are water, while dragons are creatures of air and fire, and represent the unbound power of the spirit-nature, which we all contain.

The poet's choice of creatures, fish and dragons, in the lanterns described as dancing through the night at the festival thus carries the idea of our dual nature, just as the lanterns themselves with their glowing inner candle shining within the delicate outer paper wrapper also depict an aspect of our condition in this incarnate passage through night, when we carry an inner divine spark dimly glowing through our fragile "reflecting-medium" of the body (as Alvin Boyd Kuhn describes it in the passages cited above).

The fact that this poem is "To the tune of the Jade Table" might also be a hint, in that the "Jade Table" may poetically refer not just to a specific tune about a piece of furniture but to this green table of the earth upon which we have been blown by the east wind to blossom like spring flowers on the trees, or upon which we fall as a rainstorm, even though we are (spiritually speaking) stars who come to earth from the realm of spirit.

And then there is this legend associated with the origin of the Lantern Festival itself, which says that in ancient times, a beautiful bird beloved of the heavenly Jade Emperor flew down to earth, and the people in their ignorance chased the bird and killed it. Engraged, the Jade Emperor vowed to destroy the people by raining fire down upon them, and what is more to do it upon the night of the fifteenth lunar day of the year.

The Jade Emperor's beautiful daughter heard of this terrible plan, and sent warning to the villagers of earth. One of the people, an old man who was very wise, came up with an idea to avert the storm of fire. He instructed all the people to hang lanterns on that night, so that the Jade Emperor and his heavenly army would look down and see what looked like a river of fire already blanketing the towns and villages. The old man also instructed them to set off firecrackers all night, so that the heavenly army would think that all the people were already perishing. In this way, they would no longer feel the need to rain fire down upon the villagers.

And so, the lanterns and fireworks averted the vengeance of the Jade Emperor for the loss of his favorite bird of heaven, and the event is still observed all these thousands of years later on the same night (and perhaps to ensure that the Jade Emperor continues to hold off the rain of fire -- who knows).

The story can also be found in this and other children's books describing the origin and meaning of the Lantern Festival.

Now, this story is a clear giveaway that the Lantern Festival has celestial origins and foundations, because a descending heavenly bird and fire from heaven should by now ring bells for readers who have followed some of the more than fifty "Star Myth" explanations detailed in previous posts, showing the celestial foundations of myths, scriptures, and sacred traditions from around the world.

Below is an image of the portion of the sky which I believe contains the constellations that form the foundations of this myth regarding the origin of the Lantern Festival. The heavenly view will first be presented without my explanatory markings, as it appears in the excellent open-source planetarium app from

:

Note the smoky column of the Milky Way galaxy, rising up from a point just to the left of the large red "S" that indicates the center of the southern horizon (this screen view simulates an observer in the northern hemisphere, looking towards the south). You may be able to see the curving tail of the sinuous Scorpion constellation just above the horizon, pointing right into the Milky Way.

I believe the Milky Way represents the threatened "rain of fire" from heaven, but also the celestial counterpart to the Lantern Festival that is taking place down on earth. When the Jade Emperor and his heavenly captains see the glowing river of lights from the lanterns of the people, they stay their hand and do not release the storm of fire. The Milky Way represents the lanterns of the people, which the Emperor and his commanders see, causing them to avert the threatened vengeance.

Below is the same screen-shot, but this time I have drawn in and labeled the other constellations I believe play the roles of the Bird of Heaven, the Jade Emperor himself, and his kind and lovely daughter, who warns the people:

The Bird of Heaven who flies too close to earth and is pursued and killed by the people is probably the great Eagle, Aquila. The Eagle and the Swan face one another in the Milky Way galaxy itself, and they figure prominently in many myths around the globe. For more on Eagle and Swan, and how to find them, you can check out this index of stars and constellations that have been featured in previous posts, and look for Aquila and Cygnus. It also has an outstanding image of the Milky Way as it looks rising up from the horizon to an observer out in the desert, away from city lights.

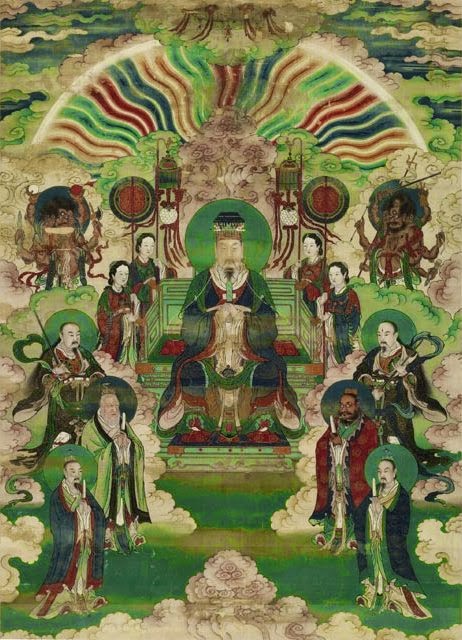

The Jade Emperor is most likely the constellation Bootes, the Herdsman. The reason I believe he is played by Bootes is the fact that Bootes is seated, as if on a throne, and the Jade Emperor is usually presented (not surprisingly) the same way (see below). In some images of the Jade Emperor, one leg is even tucked-in at a sort of "semi-cross-legged" angle, which may be reflective of the short, bent leg of this constellation.

image: Wikimedia commons (link).

Even more importantly, Bootes is a northern constellation, and one who is very close to the pivot of the heavens, the central point around which all of the celestial attendants must turn: the north celestial pole. His "pipe" reaches nearly to the handle of the Big Dipper, and the Dipper of course points to the current Pole Star, Polaris. This fact would make Bootes a strong contender for the Jade Emperor, who holds court at the very center of the heavenly dome.

Another good reason to believe that the Jade Emperor is played by the celestial giant Bootes is the fact that Bootes is very close to Virgo and appears as her father (or grandfather) in many, many Star Myths around the world (see for example this one).

We obviously have a "daughter" appearing in this story: the daughter of the Jade Emperor, who takes pity on the people of earth and warns them of her father's terrible plan. The daughter is almost certainly played by Virgo in this Star Myth about the origins of the Lantern Festival.

Connections like this in the foundational myth of the Lantern Festival indicate that its celestial significance was well understood by at least some segment of the culture down through the millennia that this annual celebration has been going on.

And so, the festival of lanterns enacted each year at the Full Moon of the first month after the lunar New Year serves an important purpose: it connects heaven and earth, and reminds us that, though we move about on this terrestrial surface (this "Jade Table") in these human bodies, we are also truly spiritual beings, from another realm not mingled with earth or water -- the realm of invisible spirit, the realm of the gods.

The lanterns and the firecrackers themselves serve to remind us and re-awaken us to that fact -- and they seem in fact to be symbols most excellently selected to do so. Below is another segment from the Ming Dynasty painting shown earlier -- in this portion, several people are setting off fireworks, and the Emperor himself can be seen enjoying the festivities from a porch above, under a yellow awning or silken tent.

image: detail from Ming Dynasty painting, late 15th century, Wikimedia commons (link).

And so, let us conclude with a final quotation from the lecture by Alvin Boyd Kuhn mentioned above, in which the spiritual significance of the moon in its phases, and the message the ancients believed that this glorious and nearest of heavenly bodies conveys to us, progressing as it does each month not only from New Moon to Full Moon and back again, but also from the western horizon (where the New Moon is first seen, trailing the sun which has "lapped it" again at each New Moon and then proceeds to get further and further "ahead" of the moon in its course across the sky) to the eastern horizon. He says of the moon:

As just seen, the new moon is conceived in the west, the region of all beginning or entry upon incarnate life, the place of descent into the underworld. It has its birth and begins its career of growth in the west, moving night by night further toward the east. Man, the soul, enters his journey toward divinity in the west, and life by life moves further toward the east, the place of fulfillment and glorious resurrection. What more fitting, then, that the rising of the moon in its full glory, when it typifies the completed and perfected human-divine, the man become god, should take place in the east, the gate of the resurrection! The young new moon appears and mounts in the west; the full moon in the east! 13 - 14.

With this added insight from Alvin Boyd Kuhn, we can now see that the "Lantern Festival Night" poem by Xin Qiji incorporates both the motion of the incarnation or the "descent into the material realm" (with its reference to the wind that moves towards the west, and which sends stars to fall down to earth like rain, or causes flowers to bloom on the trees, representative of our incarnation in these fragile physical forms which are akin to flowers or to paper lanterns) and the motion of the movement back towards the east -- the motion of greater spiritual awareness and awakening -- in the evocation of the motion of the moon from New Moon to the Full Moon, a motion during which the moon's position at the same time each night will be seen to be further and further east in the sky.

The moon is currently voyaging back towards the point of New Moon, having passed through the night of Full Moon and the night of the Lantern Festival, but it is still the "first moon" of the lunar year, and we can get up early in the morning and see it in the sky before dawn (rising less and less distance ahead of the sun each day), and think about the spiritual truths that the moon conveys to us.

In fact, we can do so throughout the year, and as we do so give thanks for the moon's constant reminder that we and the universe are composed of a physical aspect but that within each of us there is a spiritual component which we should be bringing forth in every way that we can.

One night's east wind adorns a thousand trees with flowers

And blows down stars in showers

Fine steeds and carved cabs spread fragrance en route

Music vibrates from the flute

The moon sheds its full light

While fish and dragon lanterns dance all night

In gold-thread dress, with moth or willow ornaments

Giggling, she melts into the throng with trails of scents

But in the crowd once and again

I look for her in vain

When all at once I turn my head

I find her there where lantern light is dimly shed