image: Wikimedia commons (link).

The previous post and video discussing the ancient sacred text of the Bhagavad Gita explored its celestial foundation, showing that like the rest of the world's Star Myths it uses the majestic celestial cycles as an extended metaphor portraying the descent of each human soul into this incarnate life, an incarnate life which can be seen as a sort of "battlefield" characterized by the endless struggle or interplay between the material and spiritual realms (both within the individual and without).

Immediately prior to Arjuna's descent into the battle of Kurukshetra, he is given direct guidance from his divine companion, the Lord Krishna:

Do your duty to the best of your ability, O Arjuna, with your mind attached to the Lord, abandoning worry and attachment to the results, and remaining calm in both success and failure. [. . .] Therefore, always perform your duty efficiently and without attachment to the results, because by doing work without attachment one attains the Supreme. (2.48 - 49; 3.19).

In fact, over and over throughout the Gita, Lord Krishna's message to Arjuna is basically the same: do what is right, without attachment to the results: instead of attachment to the results, the mind should be attached to the Infinite divine principle.

This Infinite supreme principle is represented in the Gita by Lord Krishna, who shows himself in the Gita to be completely Infinite, beyond definition or categorization by the mind. The same Infinite supreme principle is represented in the chapters immediately preceding the Bhagavad Gita (in the Mahabharata of which the Gita is a small but central part) by the goddess Durga, who is also described in terms which indicate that she too is supremely beyond definition or characterization or containment within boundaries (see discussion and video in this previous post).

While this advice may seem to apply only to those ascetics who withdraw from the hustle and bustle of the daily struggle to make a living and negotiate the mundane world of keeping the dishes washed or the faucets from leaking, I believe that it may well have been given for the benefit of all of us here in this incarnate realm, even if we do not personally dress in flowing robes and retire to a life of full-time meditation and study of the Vedas (although of course it would be of great benefit to us in that particular path of life as well).

Consider, for example, the possibility that some of our greatest times of frustration and anger seem to come at moments when we experience serious self-doubt (such as when changing out the above-mentioned faucet, if that is a task we're not really sure that we will be able to do properly, and we don't have confidence that it will turn out no matter how many times we consult helpful internet videos purporting to show us what to do). It is in those situations (I find) that we seem to be most prone to lashing out (even if we are "only" lashing out at an inanimate faucet, or the entire unfair world of faucets and water-fixtures -- the things we say to inanimate faucets, bolts, washers, and threaded fasteners can in fact be quite ugly and embarrassing to us in later recollection, and things we certainly hope that the neighbors did not overhear).

Or, consider a classic hero in any of your favorite old kung fu movies: if he or she is completely confident in his or her ability to handle the situation, the kung fu master will not show the slightest bit of anger or frustration -- while the villain (who secretly fears he may not be able to handle the abilities of his opponent) gets angrier and angrier and eventually bursts out in a display of rage which lets the audience know that he is in fact about to lose.

Wouldn't we all desire to arrive at the place where we are like that hero in the kung fu movie -- totally secure in our knowledge that we can handle the situation at hand (any situation whatsoever), and therefore completely unflappable and beyond anyone's ability to make us "lose it"?

As we all know, however, the material world seems to be custom-designed to defy the possibility of any one mortal human to have such kung fu (and such knowledge of plumbing repair, automotive mechanics, personal finance, parenting, golf-ball physics, etc) that no situation can ever arise which would be beyond their ability.

And yet it may well be that Lord Krishna in the Bhagavad Gita is specifically telling us that no matter the situation in which we find ourselves, we can in fact transcend both the heart-clutching self-doubt and the attachment to results that can cause us to fly into a rage (or otherwise say and do and think things which we later regret), and instead become more and more like that enlightened kung fu master in the old movies (as an important side note, some of the asanas of yoga, which are basically impossible to accomplish at first try but which can eventually be achieved after years of disciplined practice, may be teaching this very same thing).

Again, I believe it is very possible that the lessons imparted to Arjuna prior to the great Battle of Kurukshetra are given to us not only for helping us in the extraordinary circumstances or extreme situations in which we might find ourselves, but in ordinary and mundane aspects of everyday life (including changing a faucet, or parenting).

Even if most of us have not reached the level of the kung fu master for whom no situation could ever arise beyond our personal capability, by following the Bhagavad Gita's directive of doing what is right, to the best of our ability, and attaching our mind to the Infinite -- to which we, in fact, always have immediate access -- we can replace that clawing self-doubt with something completely different.

This may seem to be just too simple, but it may in fact be one of the primary things we are supposed to be practicing here in this material world. Remember, this one piece of advice is in fact the central message that Krishna offers to Arjuna, over and over throughout the Bhagavad Gita, in a variety of different ways.

And, it certainly does not seem to me to be extremely simple to do consistently, even for one single day. First, it is not always perfectly obvious what it means to "do what is right" or "do your duty" in every possible situation -- we are often pretty good at rationalizing our way out of doing what is right, coming up with excuses to tell ourselves in order to excuse ourselves from doing what we know we should do, as the figure of the blind king Dhritarastra demonstrates very graphically in the Mahabharata.

In fact, the character of Dhritarastra seems to embody a powerful warning against trying to distort the actual Bhagavad Gita message of "do what's right without attachment to the results" into the false message of "use 'fate' as an excuse to avoid doing what's right," or "leave it all to fate (without attachment to the results)."

The Mahabharata portrays Dhritarastra's abdication of his responsibility to restrain evil as directly responsible for the chain of events that bring about the Battle of Kurukshetra in the first place. In this case, Dhritarastra fails to curtail the wicked schemes of his own son, and because as the king and the father everyone else defers to him as the one who should act, things get progressively further out of hand.

Dhritarastra, for his part, consistently declares that all is in the hands of fate, and so he has to accept the outcome. For example, at the end of Book 2 and Section 48, in response to the urging of his wise brother Vidura to stop the disastrous dice game which will eventually lead to the enmity that brings about the cataclysmic battle, Dhritarastra defends his refusal to do his duty by saying,

Therefore, auspicious or otherwise, beneficial or otherwise, let this friendly challenge at dice proceed. Even this without doubt is what fate hath ordained for us. [. . .] Tell me nothing. I regard Fate as supreme which bringeth all this.

The ancient scriptures, through the events in the Mahabharata, appear to be showing us that this attitude of Dhritarastra is a perversion of what the Bhagavad Gita teaches: it is not "avoid your duty and abandon attachment to results" but rather "do your duty, to the best of your ability, without attachment to the results."

Because the Mahabharata is using metaphors to convey spiritual teachings, it makes Dhritarastra (whose character I believe to be a metaphorical figure meant to depict an aspect of our human experience in this incarnate life, and not a literal historical king from the ancient past), a blind king, whose failure to see the right course of action and his resulting failure to do what is right lead directly to the disastrous battle between two sides of the same family.

But, the Mahabharata elsewhere tells us in no uncertain terms that this metaphorical blindness is exactly our condition when we plunge into material existence, until we regain our connection to the Infinite -- which is actually within us and thus potentially available to us at any time, in any situation.

In a fairly short passage found very early in the epic, in Book 1 and Section 3, the Mahabharata gives us the story of a spiritual disciple named Upamanyu, who out of hunger eats leaves from a tree which cause him to go blind. Crawling around on the ground in his blinded condition, Upamanyu proceeds to fall right into a deep well, where he winds up alone, at the bottom of a well, blind.

After his spiritual teacher notices his absence and comes looking for him and calling out his name, Upamanyu answers from the bottom of the well. His teacher comes to the top of the well and asks what has happened: Upamanyu relates the story of his having eaten leaves from a mighty tree, which caused him to go blind, and then fall to the bottom of the well.

The Mahabharata tells us that the teacher says:

"Glorify the twin Ashvins, the joint physicians of the gods, and they will restore thee thy sight." And Upamanyu thus directed by his preceptor began to glorify the twin Ashvins, in the following words of the Rig Veda:

"Ye have existed before creation! Ye first-born beings, ye are displayed in this wondrous universe of five elements! I desire to obtain you by the help of the knowledge derived from hearing, and of meditation, for ye are Infinite! Ye are the course itself of Nature and intelligent Soul that pervades that course! Ye are birds of beauteous feathers perched on the body that is like to a tree! Ye are without the tree common attributes of every soul! Ye are incomparable! Ye, through your spirit in every created thing, pervade the Universe! Ye are golden Eagles! Ye are the essence into which all things disappear! Ye are free from error and know no deterioration! Ye are of beauteous beaks that would not unjustly strike and are victorious in every encounter!"

And Upamanyu's glorification of the Ashvins continues, until the text tells us that "The twin Ashvins, thus invoked, appeared" and restore Upamanyu's sight, and give him a blessing and tell Upamanyu that he shall have good fortune.

Clearly we have here another illustration of the importance -- and the immediate availability -- of the connection to the Infinite. This time, instead of Lord Krishna representing the supreme Infinite or the goddess Durga representing the Infinite, it is the twin Ashvins who are specifically described in terms that indicate that they themselves are beyond categorization, that they are themselves the Infinite and undefinable and unbounded (at one point in the hymn of praise, Upamanyu says that they are both males and females, that they are the givers of all life, and that they are the Supreme Brahma).

And, just as in our previous examination of the Bhagavad Gita we saw clear evidence that Lord Krishna is associated with the celestial figure of the constellation Bootes the Herdsman (as Arjuna the semi-divine archer is associated with the celestial figure of Orion), and just as in our previous examination of the Hymn to Durga we saw clear evidence that the goddess is associated with the zodiac constellation of Virgo the Virgin, in this story of Upamanyu and the Ashvins, we see clear evidence of celestial metaphor at work as well.

The twin Ashvins very clearly correspond to the zodiac constellation of Gemini the Twins, who are located near the "top" of the shining column of the Milky Way galaxy. The Milky Way actually makes a complete ring in the sky, with one half of the ring visible primarily during the summer months and the other half during the winter months: when the part of the Milky Way that the Twins appear to guard (with Orion right nearby) is visible in the sky, the other half (it's "lower end") is not visible, and vice versa. On the other side of the celestial sphere, the Milky Way band is guarded by the constellations Scorpio and Sagittarius. When the Twins and Orion are in the sky, Scorpio and Sagittarius are not (because nearly 180 degrees offset on the celestial sphere), and when Scorpio and Sagittarius are in the sky, then the Twins and Orion cannot be seen.

Below are two frames from the Stellarium digital planetarium app, showing a southern-looking view for an observer in the northern hemisphere, looking at each of the "two sides" of the great Milky Way ring as it rises up from the southern horizon, at two different times of the year. On top is shown an image of the "upper reaches" of the Milky Way column (flanked by the Twins and Orion), and immediately below that is an image of the dramatic "base" of the Milky Way column (with Scorpio drawn in, lurking at the very bottom).

The constellations which I believe figure most prominently in this episode of Upamanyu and the Ashvins are given colorful outlines for ease of identification: if you want to see the same screen-shots without the colorful outlines, I have provided them at the bottom of this post, in the same stacked order (the Twins-side of the band in the top image, and the Scorpio-side in the lower image).

I believe that it is pretty clear that celestial representation of the "well" into which Upamanyu falls when he is blinded by the leaves of the tree is in fact that shining column of the Milky Way itself. Way up at the "top" of the column, we see the Twins of Gemini -- representing in this particular myth the helping deities of the Ashvins, who dwell in the realm of spirit but who will appear immediately when invoked by Upamanyu.

At the very bottom of the column we see the helpless figure of the Scorpion, who may well represent Upamanyu in his blinded condition (there are other important myths in which a figure associated with Scorpio is temporarily blinded, but in any case, we know that Upamanyu is located somewhere at the bottom of the well, which is where Scorpio is to be found).

When Upamanyu's teacher calls down to him in the well, the teacher may be "played" in the myth by the constellation Orion, who is also located (like the Twins) near the "top" of the well when Upamanyu is at the bottom.

In his praise and invocation of the Ashvins, Upamanyu declares that they are many things: they are both males and females, they are the parents of all, they are the ones who set in motion the wheel of time -- which wheel is itself described in imagery which parallels very closely the image of the wheel with "strakes" that is described in the famous Vision of the Prophet Ezekiel in the Hebrew Scriptures.

He also describes them as beautiful birds, as golden Eagles, who have perched on something that is very "like to a tree" -- undoubtedly, this is another celestial clue to help us decipher the constellations underpinning this text. The two birds on the body that is like a tree are the two majestic constellations of Aquila the Eagle and Cygnus the Swan, both of whom are above poor Upamanyu at the bottom of the well.

What is going on here? What is the message?

I believe that this story of Upamanyu, with all of its celestial trappings, is a condensed allegory of our human condition in this incarnate life -- the kind of spiritual teaching that the ancient scriptures almost always try to convey using celestial imagery.

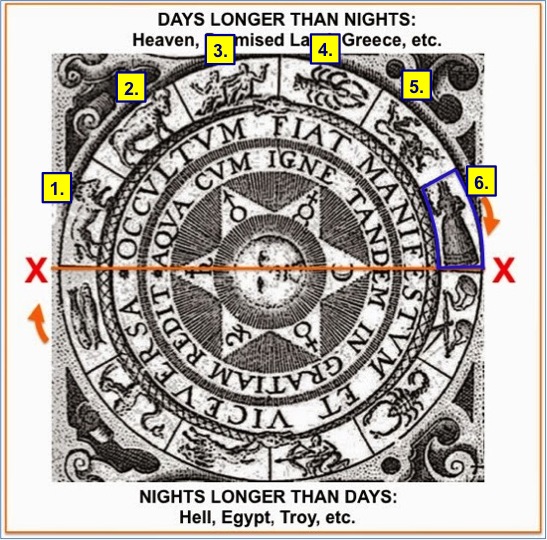

We are cast down into incarnate, material existence in a human body like Upamanyu falling down a deep well. The plunge down into the lower realms of matter is associated with the lower half of the zodiac wheel -- where Scorpio and Sagittarius basically "guard" the lowest point on the annual cycle, just prior to the winter solstice (see the now-familiar zodiac wheel diagram, used in countless previous posts, below):

In this incarnate condition, we are like prisoners at the bottom of the wheel -- like Upamanyu deep at the bottom of the well. We are also spiritually blind, prone to falling prey to all the many attachments and errors against which the Mahabharata and the Bhagavad Gita warn us.

And yet at some point there comes a turn -- a turn in which we look to the realm of spirit, to the connection with the Infinite which has in fact been available to us all along (because we are not, in fact, entirely animal or entirely material, but have within ourselves a divine spark, an inner connection to the Infinite).

When Upamanyu invokes the Ashvins, he is calling to the ones who are located at entirely the other end of the wheel -- at the top of the cycle, in the upper realms of fire and spirit, and at the very top of the Milky Way column that can be envisioned as running from the bottom or "6 o'clock" position on the above zodiac wheel right up to the top or "12 o'clock" point on the circle, right next to the Twins of Gemini.

And so, when we look at Dhritarastra in the Mahabharata, and his disastrous failure to do the right thing, we must realize that he also does not represent an external king who lived thousands of years ago, but that he (like Upamanyu) is meant to depict one aspect of our human condition.

He is frequently wracked by self-doubt, and he also needs to be warned against the specific errors of wrath and anger by his wise brother Vidura, in Book 5 and Section 36 for example. His disastrous (even if often understandable and even at times well-meaning) failure to do what is right is a depiction of our own typical condition in this incarnate existence (as is Upamanyu when he becomes blind and falls down into the well).

But, although we are in this condition down here at the bottom of the well, we actually have access to the Infinite, right where we are -- as Upamanyu demonstrates when he calls upon the Ashvins and they appear, and restore his sight. This is depicted as the solution to our plight: connection to the Infinite, with which we in fact are already connected, if we could only see it (and even Dhritarastra later invokes through meditation the same connection to the infinity of the invisible realm, which is depicted in the illustration at the top of this post).

In fact, this is the only source of rescue depicted in the text. It is not Upamanyu's wise teacher who rescues Upamanyu: it is Upamanyu's wise teacher who tells Upamanyu to call upon the Ashvins. It is the connection with the Infinite that Upamanyu must achieve or restore in order to escape or transcend the condition in which he originally finds himself at the bottom of the well.

This is in fact identical to the message that Lord Krishna gives to Arjuna in the Bhagavad Gita, and identical to the message depicted in the invocation of Durga immediately prior to the Bhagavad Gita. All three parts of the Mahabharata are in fact telling us and showing us the very same message -- they are just employing different metaphors (and different celestial entities, whether Bootes, Virgo, or the Twins of Gemini) in order to convey that message.

And so, I hope, this discussion helps to remind us that these teachings are for all of us, all the time. The esoteric metaphors in the Mahabharata and the Bhagavad Gita are not just for full-time yogis, or kung fu masters, or those facing extraordinary circumstances. We have all of us eaten from the leaves that have temporarily blinded us, and we have all of us fallen into a deep well, so to speak.

If that is the case, then these teachings are for everyone who finds himself or herself cast down into this physical existence, this deep well (which is, I'm sure, just about everyone who is reading this blog right now).

The solution is simple, but it is one that can occupy us for a lifetime. In the words of the ancient text:

Do your duty, to the best of your ability, with your mind attached to the Lord [to the Infinite, to the goddess Durga, to the twin Ashvins, to Krishna the divine charioteer], abandoning worry and attachment to the results, and remaining calm in both success and failure.

(below are the screenshots of the Milky Way band, with the Ashvins on top and Upamanyu at the bottom of the well, without the annotated constellation outlines):